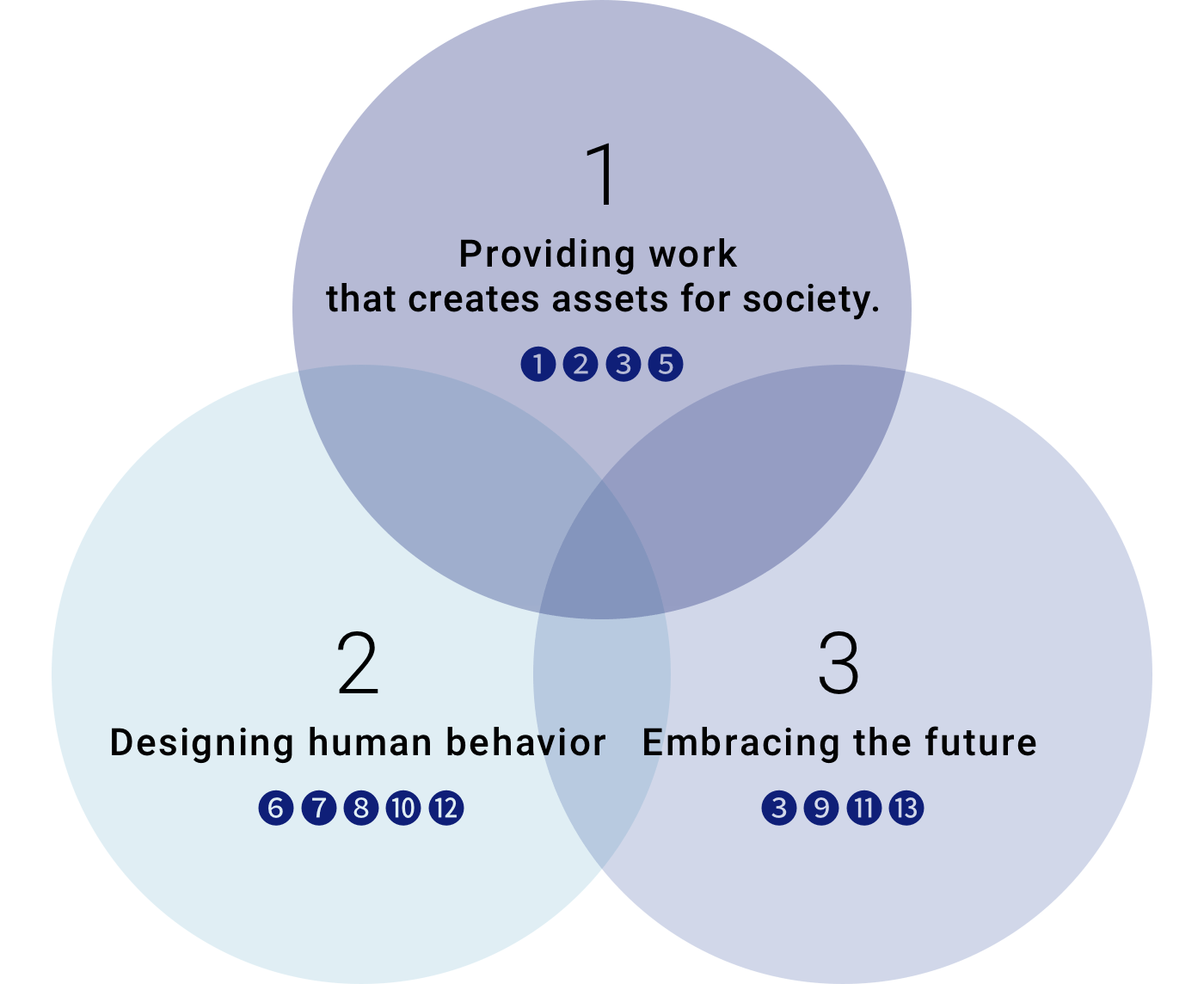

- 1. Providing work that creates assets for society.

- Just as many of founder Gunpei Matsuda’s works have remained in pristine condition for over eighty years, we also aim to create buildings that will outlive us. As designers and architects, it is our responsibility to creates lasting assets for society. We do so by treating people as paramount and thinking closely about what the essence of a building ought to be, developing evergreen worksthat continue to contribute to society.

- 2. Designing human behavior

- Architecture firms do not engage solely in the design of the shapes and forms of buildings. Far and away more important than that is designing how people will use these structures and engage with and within them. Good architecture can usher in positive lifestyle and workstyle changes and transform people’s attitudes and awareness. People are always our focus, first and foremost.

- 3. Embracing the future

- We do not shy away from challenges, even when there is no blueprint to the future. Trying new things is par for the course at MHS. Founder Gunpei Matsuda brought home to Japan cutting-edge technology that he had gained exposure to in the United States. Just as he updated the very history of Japanese architecture, so, too, do we value the unknown and inherit this enduring ethos of boldly venturing into new territory.

1. Providing work that creates assets for society.

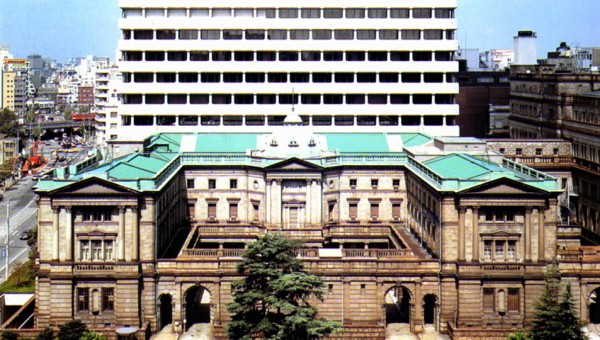

- 1. Mitsui Honkan/1929

- This project was the maiden voyage for founder Gunpei Matsuda. He was engag+G10ed in a design project in the United States on the night before founding the firm, and assumed a position as deputy site supervisor upon his return to Japan. Drawing on all of the new knowledge he had absorbed in the United States and leveraging it to the fullest, he aimed to create edifices that would become lasting assets for society. In 1998, this structure was designated as a nationally important cultural property.

Approaches gleaned from this project

This project would pave the way for other edifices that would undergird the social fabric of Japan, such as the Bank of Japan and leading mega banks.

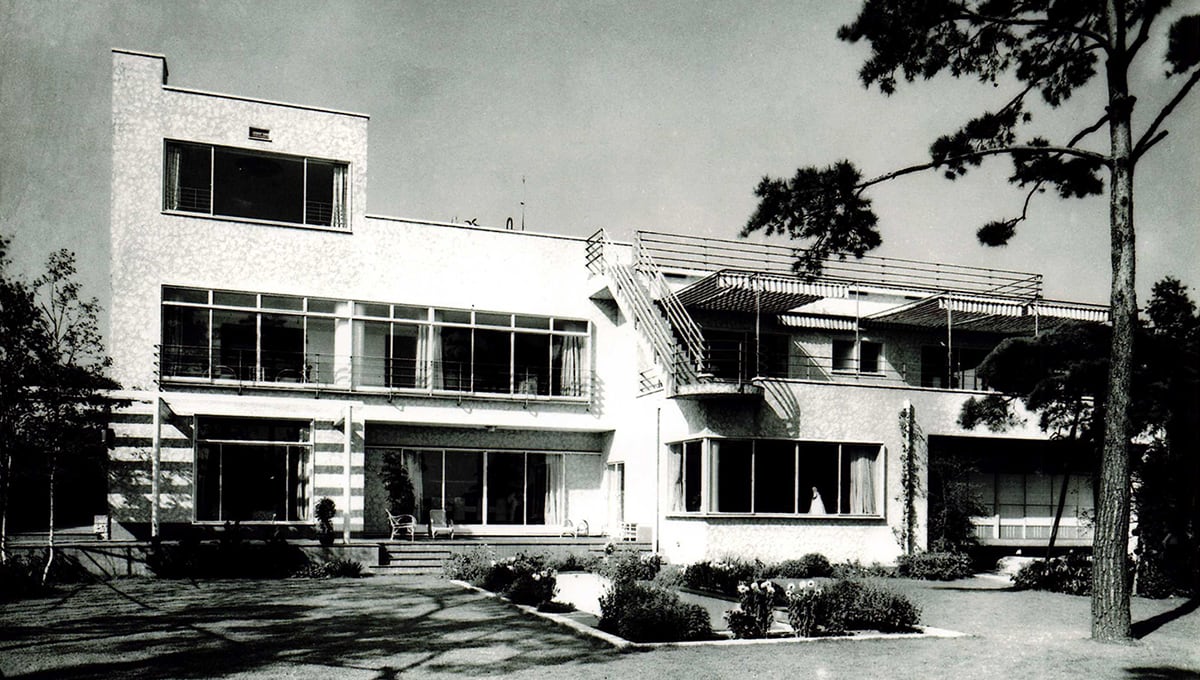

- 2. Shojiro Ishibashi residence/1931

- This was the private home of Shojiro Ishibashi, founder of Bridgestone Tires. Today, it serves as the residence of the ambassador of the United States to Japan and retains a stately appearance. The facade is strongly inspired by modernism, with interiors incorporating art deco elements. This unique home has become a signature residence for the ages.

- 3. Tokujiro Ishibashi residence/1931

- Today, this serves as the Ishibashi Guest House. Following renovations in 1957, many of the techniques employed at the time of its construction were preserved, ensuring that it exudes a unique modernist atmosphere still today. The house is highly evaluated for the Spanish-style exterior, the exquisite blend of Japanese and Western sensibilities in the interior, and the technical skill of the artisans who were engaged in its creation.

- 4. Izu villa of Takanaga Mitsui/1934

- This building was constructed as a private villa for the Mitsui family. In 1971, it was converted to the Suzaki Imperial Villa. This Spanish-style villa is strongly influenced by the work of the John Russell Pope architectural firm, where Gunpei Matsuda worked in New York.

2. Designing human behavior

- 5. Bridgestone headquarters/1952

- This American-style office building was constructed soon after WWII. Bridgestone was one of the first companies to employ American air conditioners to create a more comfortable workplace. The Bridgestone Museum of Art is also located here. This workplace has become a cutting-edge space in which the office is interlinked with a gallery.

Approaches gleaned from this project

This building proved to be a frontrunner in designs focused on the well-being of workers, and inspired modern-day structures like the Jingumae Tower Building.

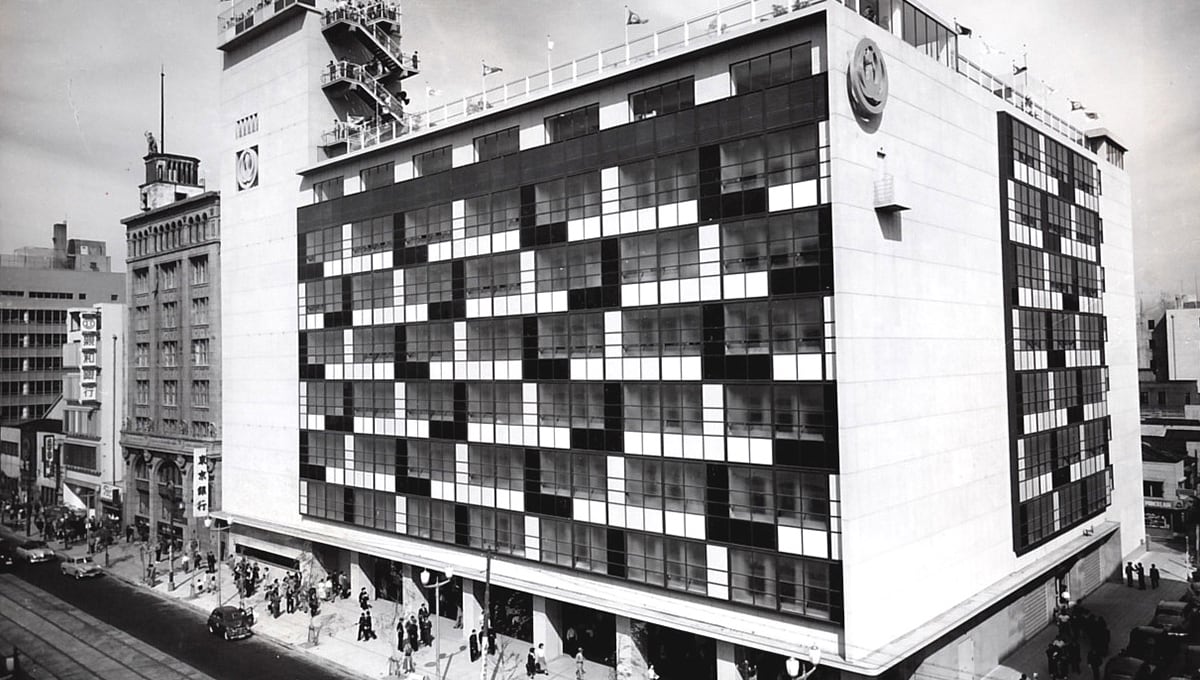

- 6. Matsuya Ginza/1953, 1964

- This is one of Japan’s signature department stores and has been in operation since the Taisho period (1912-1926). The firm was responsible for remodeling the entire building after WWII. Going shopping in Ginza, the premier district for commerce, was a special occasion for everyday people in those years, and the firm used a modern design to convey the importance of the occasion. The firm was also responsible for major renovations performed in advance of the Tokyo Olympics. The exterior framework is still in use today.

- 7. Tamagawa Takashimaya Shopping Center/1969

- This was Japan’s first large-scale shopping center, built on the suburbs of Tokyo. It incorporated flourishes like a large parking lot and was designed with an eye to the coming motorization of Japanese society. It continues to grow and evolve to this day. This was a frontrunning suburban shopping center that would presage many similar developments to come.

- 10. Sotetsu Joinus/Yokohama Takashimaya/1973

- This shopping facility forms a part of the Sotetsu Building, a train station concourse building located at the west exit of Yokohama Station. During Japan’s period of rapid economic growth, more and more commercial facilities became integrated into train station environs, with the buildings being extended and structurally altered. These buildings have continued to evolve side by side with the growth and development of the cities around them.

Approaches gleaned from this project

The firm’s commitment to creating a commercial facility that would be beloved by consumers for years to come (while incorporating cutting-edge touches) is an ethos we continue to use In the design of shopping facilities today that present something new to the consumer.

- 12. Tokyo International Air Terminal/1964

- The original Haneda Airport Terminal played a pivotal role in acting as the “doorway to Japan” as the country’s first international terminal. In those days, it was unusual for architectural designers to take part in planning an airport, but Gunpei Matsuda brought back to Japan the American way of working and collaborated with other architects on the early stages of the airport plan. MHS was also responsible for the design of the building.

3. Embracing the future

- 8. Bridgestone Tires Kurume Plant/1933

- This was the first Bridgestone Tires plant in Japan. It has acted as a pivotal part of the Bridgestone group of companies’ production infrastructure for over seventy years. Pillars with capitals were employed in order to eschew beams and create a more spacious interior. This outstanding flexibility gave the building longevity and has allowed it to remain relevant into the present.

Approaches gleaned from this project

Enhancing the flexibility of the structure has allowed it to grow into a production and logistics center that continues to be used today. This forward-thinking approach remains an abiding part of the firm’s process.

- 9. New Shinbashi Building/1971

- This was one of the linchpins in our work involving the redevelopment of buildings. It became a frontrunner in new techniques for urban redevelopment and played a role in sprucing up the area around Shinbashi Station, which had become a sprawl of unlicensed, black market shops. The design sought to respect and maintain the lifestyle and livelihood of local residents while improving ease of use and safety of the area. This would become an abiding technique in urban planning projects used to this day.

Approaches gleaned from this project

This project saw the firm becoming involved in the early urban planning and design stages, an approach that is alive and well today in our redevelopment projects and plans for reconstruction of apartment complexes.

- 11. Fuji Bank Nakameguro Center/1974

- The central courtyard here provides a place of respite for workers. The design was contemporary in its vision and sought to create a workplace environment that was comfortable and intuitive. It also incorporates double skin facades, a technique drawing attention in recent years for its ability to improve the energy efficiency of buildings.

Approaches gleaned from this project

The firm’s dedication to achieving environmentally-friendly structures while achieving a comfortable space has been achieved through works such as the new government buildings in Kaisei, Kanagawa Prefecture, the first of their kind to receive ZEB certification. These insights continue to be used in other environmentally-aware designs.

- 13. Former Nakayama Racecourse stands/1960

- In an age when the large roofs covering racecourse stands were supported by unwieldy pillars, we introduced a cantilevered solution. This approach cleared visual obstructions for the spectator and provided them with a space in which to engage more deeply with the race. We continue to develop advancements in this area today.

Approaches gleaned from this project

In projects like the Tokyo Racecourse, which employs the world’s largest cantilevered stands, protruding at 45 meters out to enhance the view of the race, and the International Stadium Yokohama, with capacity for over 70,000 people, we carry on this tradition of excellence.